Charles D. Bernholz, Love Memorial Library, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588 [*]

Robert J. Weiner, Jr, H. Douglas Barclay Law Library, Syracuse University College of Law, Syracuse, NY 13244 [**]

Abstract

Charles J. Kappler (1868–1946) is known primarily for his compilation, Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. His life, however, reached beyond this accumulation of fundamental documents. He was a staff member of, among other entities, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs; served as co-counsel in the first case before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague; brought important tribal issues before the courts, just a quarter century after the Battle of the Little Big Horn; married, was widowed, married again, developed a family, and found a place in District society; and, in one role or another, participated in a number of major Indian law cases before the United States Supreme Court, prior to the creation of the Indian Claims Commission.

(The Amiable Isabella, 1821, p. 71).

The study of the relationships formed between the federal government and the American Indian tribes has been a subject of national interest for over two hundred years. A fundamental asset to such examinations is the array of 375 treaties, recognized by the Department of State and the courts, [1] which link together these sovereigns.

For the last century, a major source of the final texts of most of these instruments has been the compilation of Charles J. Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties (1904a–1941), a collection that, at Kappler's death, was described as "a five-volume reference work accepted as authoritative by the highest courts" (Charles Kappler Dies; Expert and Writer on Indian Affairs, 1946). [2] Volume 2, with the content of these negotiations, has been especially useful (Kappler, 1904b). Digital conversions of his work, and of the few treaties not included in his volumes, have made these materials even more accessible (Bernholz and Holcombe, 2005; Bernholz, Pytlik Zillig, Weakly, and Bajaber, 2006).

Few realize, however, that following his service with the federal government during which he began to assemble Indian Affairs, Kappler was deeply involved in proceedings before various jurisdictions that centered upon these very documents. His efforts on behalf of the tribes, in fact, led to his adoption by the Crow.

Charles J. Kappler was a life-long resident of Washington, DC, commencing with his birth on 16 November 1868, the son of German immigrants Anton and Suzanna (née Walter), a shoemaker and housewife (Leonard, 1925, p. 803). [3] The 1880 Census record indicates siblings consisting of two older brothers (Frank and Henry), a sister in between these two (Mary), and one younger sister (Annie) (Department of the Interior, 1880a). Kappler "graduated from public and parochial schools of the District" (Charles Kappler Dies; Expert and Writer on Indian Affairs, 1946) and then studied stenography and typing with Theodore F. Shuey, the dean of Congressional reporters at that time (Charles Kappler is Authority on Indian Laws and Treaties, 1941; Heckel, 1968).

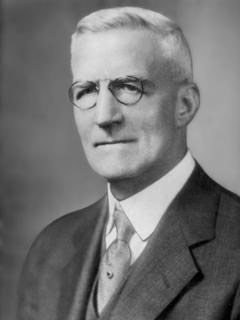

Charles J. Kappler, 1868–1946

(Star Collection, DC Public Library; © Washington Post)

After these studies, and while working as secretary to Senator William M. Stewart (1827–1909; R-Nevada) — an administrative post held years earlier by Mark Twain [4] — Kappler became involved with irrigation issues, stimulated by his participation in Stewart's two month fact finding odyssey through the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Nevada, California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas in the Fall of 1889 (see Mack, 1964, pp. 78–80). [5] The group was accompanied by the second Director of the United States Geological Survey, Major John Wesley Powell. During a tough Senate campaign, Stewart had Kappler speak publicly of the Senator's achievements (Kappler, 1892) and make the presentation speech at the University in Reno for a portrait of the Senator (Presentation of Senator Stewart's Portrait, 1892); both opportunities were good practice for his future law endeavors. Besides his service to Stewart, Kappler graduated from the Law School at Georgetown University with his LLB degree in 1896 and LLM the following year. [6] He was admitted to the Bar in 1896 and to the United States Supreme Court in December of the same year (New Lawyers Admitted to Bar, 1896; Kappler, 1896 and 1901).

Kappler also, for a time in 1897, managed Stewart's Silver Knight-Watchman newspaper while the Senator tried to find funds to assure its survival; the paper failed in 1899 (Elliot, 1983). When Stewart became Chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs for the 57th and 58th Congresses between 1901 and 1905, Kappler served as Clerk to that Committee and became more involved with federal Indian law. [7]

For several years prior to 1901, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs included a request in his annual reports to Congress for an accurate and current compilation of the treaties, laws, and executive orders pertaining to Indian affairs (see Annual reports of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1899, Indian Affairs, Part I, 1899, p. 75). [8] Stewart submitted a resolution to create a collation of pertinent materials (Compilation on Indian Affairs, 1902a) and steered the process through the Senate (Compilation on Indian Affairs, 1902b; Treaties, laws, etc., relating to Indian affairs, 1903). The resolution initially met with some resistance by Senator Eugene Hale (1836–1918; R-Maine), who objected to the endeavor if it was to require additional funds to produce, citing other subject collections that resulted in inferior, poorly indexed works. Hale's concerns were assuaged by Stewart, who pledged the work would be "accurate, well-indexed and [have] the approval of the Interior Department" (Compilation of Indian Affairs, 1902b, p. 5664). Kappler — beginning in 1903, and continuing until 1941 while he practiced law — compiled his five-volume Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties to assemble the relevant but widely scattered materials in this area (Charles Kappler is Authority on Indian Laws and Treaties, 1941). The treaties alone were easily accessible because all but nine of the recognized documents were published in ten volumes of the Statutes at Large, [10] but a concurrent resolution in December 1903 assured the availability of all these collected materials in a single source (Indian treaties, 1904).

Further, Kappler served as co-counsel in 1902 in one of the earliest international arbitration cases, Pious Fund of the Californias v. Mexico, the first case before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. [11] Senator Stewart and Kappler submitted a Statement on Behalf of the United States to the Court (Appendix II, 1903, pp. 245–261), [12] and Stewart began the oral presentations in the case that lasted ten days (Opening Arguments In Pious Fund Case, 1902; Elliott, 1983, p. 236). [13] This supplement augmented a section in a volume of Foreign Relations of the United States that collated the correspondence associated with the Pious Fund case (Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, with the annual message of the President transmitted to Congress December 2, 1902, 1903, pp. 738–786). After Stewart's departure from the Senate in March 1905, Kappler opened the Kappler & Merillat law office [14] with Charles H. Merillat [15] and worked in this partnership [16] until 1913 when he began to practice alone. [17]

In August 1914, Kappler married Katherine Shuey, and they had two children, Suzanne [18] and Charles. [19] Katherine's father was the famed Senate reporter for the Congressional Record, Theodore F. Shuey, mentor of Kappler. Shuey's long service — 61 years at that instant — was commemorated in a 1930 Time magazine article; he was 85 years old at the time (Reporter's Birthday, 1930). He died a few years later, and his obituary declared that he had seen "all inaugural rites since 1869" (T. F. Shuey, Senate Aid 65 Years, Dead, 1933). Katherine Kappler died as the result of cancer in May of 1949 (Certificate of Death, 1949). Her obituary indicated that she had had an active life, including her long-time participation in the Washington Club, a ladies' private social club for literary and educational purposes founded in 1891 (Mrs. K. Shuey Kappler Dies Here at 61, 1949), and her involvement in current issues such as the "great sociological movement," birth control (Birth Control Wins Favor, Group Told, 1940, p. X12).

Both Charles and Katherine had been married previously. Charles had wed Isabel ("Belle") Johnson on 5 November 1896 (Marriage Registry, 1896; Social and Personal, 1896); there is a record of two real estate transfers (The Legal Record, 1905a and b) concerning lots in Widow's Mite, one of the original eighteen parcels of land that eventually became the city of Washington (Some Facts About the 'Widow's Mite,' 1921). This area held within its 600 acre boundaries today's Dupont Circle; Senator Stewart lived nearby in "Stewart's Castle," constructed in 1882 (A Short History of a Very Round Place, 1990). Belle is cited alone in other transactions (Real Estate Transfers, 1899; The Legal Record, 1906). There is even one legal notice that listed her sole participation in one business deal, along with a record of the two of them completing another (Real Estate Transfers, 1909). She died on 8 July 1912, after a year-long bout with pernicious anemia (Certificate of Death, 1912; Died, 1912). Katherine had married Holbrook Bonney on 16 February 1909 (Miss Shuey a Bride, 1909) and had divorced him in January 1914 (Wins Her Divorce, 1914).

During his career as an attorney, Kappler's specialties included Indian, mining, oil, and land law, and he represented various Indian tribes before both the Court of Claims and the Supreme Court. His service to the Crow led to his adoption by that tribe in 1931 (Charles J. Kappler, Prominent Washington Attorney, Adopted into Crow Indian Tribe, 1931). [20]

Kappler died of heart failure on 20 January 1946 (Certificate of Death, 1946; Charles Kappler Dies; Expert and Writer on Indian Affairs, 1946) and was interred at the Oak Hill Cemetery. [21]

Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, 1904–1941

It would be a disservice to speak of Kappler's life without commenting briefly upon his compilation, Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Throughout the eighteenth century, preservation of the various treaties created between the federal government and the tribes was not of major importance. Three prior efforts to assemble these legal materials included Indian Treaties, and Laws and Regulations Relating to Indian Affairs (1826); Treaties between the United States of America and the Several Indian Tribes, From 1778 to 1837 (1837); and A Compilation of All the Treaties between the United States and the Indian Tribes Now in Force as Laws (1873). As noted earlier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs William Atkinson Jones had proposed in 1899 and 1900 a new, up to date collection. In a portion of his 1900 Annual Report entitled "Needed Publication on Indian Matters," he remarked that the 1873 attempt was "inaccurate" and that "[t]he demand for a publication that shall contain all ratified treaties and agreements made by the United States with the Indian tribes is increasing. It would be in constant use in this office and would be frequently referred to by other Government bureaus and by members of Congress as well as by the public at large" (Annual reports of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1900. Indian Affairs. Report of Commissioner and Appendixes, 1900, p. 50). Jones repeated this recommendation for a third time in the 1901 Annual Report (Annual reports of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1901. Indian Affairs. Part I. Report of the Commissioner, and appendixes, 1901, pp. 46–47), repeating much of what he had said the year before. When Senator Stewart defended his resolution for a fresh attempt in May 1902, he recalled these requests when he stated that "the Secretary of the Interior has recommended for several years a compilation of treaties and Executive orders" (Compilation on Indian Affairs, 1902b, p. 5664).

As directed then by the Senate's decision to proceed, Kappler, as Clerk for the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, compiled these relevant yet dispersed materials. The first two volumes, as Senate Document 452 and for data through 1 December 1902, were published in 1903, as successive Serial Set items. Volume 1 consisted of "Statutes, executive orders, proclamations, and statistics of tribes." It was released as the 1,169 page Serial Set volume 4253. Volume 2, comprising the treaties, in Serial Set volume 4254, contained 832 pages (Kappler, 1903a and b). Funding for this work was included in the March 1903 appropriations bill: "[t]o pay the persons who compiled and indexed the two volumes of the treaties, laws, Executive orders, and so forth, relating to Indian affairs, under Senate resolution of May twentieth, nineteen hundred and two, five thousand dollars of which said sum so much as may be necessary, may be expended as additional pay or compensation to any officer or employee of the United States, to be immediately available, and to be paid only upon vouchers signed by the chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs of the Senate" (An act making appropriations for the current and contingent expenses of the Indian Department and for fulfilling treaty stipulations with various Indian tribes for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, nineteen hundred and four, and for other purposes, 1903, p. 1000).

The following year, the same materials were republished as Senate Document 319, with changes to their formats (Kappler, 1904a and b). Kappler noted in the preface to the second edition (1904a, p. v) that "[t]he new edition has afforded the compiler an opportunity to make such typographical and other corrections as were discovered in the first print, to insert several treaties and documents which were heretofore unobtainable, and to add the signatures subscribed to each treaty which was omitted in the first edition to save space." The new set of volumes was accessible as Serial Set volume 4623 and 4624, with the second volume, now including signatures, extended to 1,099 pages.

Three later volumes appeared: Senate Document 719 (Kappler, 1913; Serial Set 6166); Senate Document 53 (Kappler, 1929; Serial Set 8849); and Senate Document 194 (Kappler, 1941; Serial Set 10458) as volumes 3 though 5, respectively, with relevant contemporary federal Indian law materials. At the point when the fourth volume was ordered to be printed (Printing of manuscripts relating to Indian affairs, 1928), the Senate Committee on Printing noted that the three previous volumes were "widely used" (p. 1) and that the Secretary of the Interior, Hubert Work, had declared in 1925 that "[t]he compilation of Indian laws and treaties is constantly used and referred to in this department and the office of Indian Affairs, as well as at the several Indian agencies, where the Statutes at Large are not always available" (p. 2) . Later, publishers other than the Government Printing Office created versions for these collations. Further, the second or treaties volume was printed as a stand-alone publication (Kappler, 1972a, 1973), and a new set of all five volumes was offered in 1972 (Kappler, 1972b).

The second volume of final treaty texts has been particularly useful since its publication, because the stream of court cases addressing Indian issues began in earnest at the turn of the twentieth century. Many important cases had occurred earlier, but the handling of Indian affairs in the new century, of the tribes' assertions of their rights promised by these treaties, and of their claims against the government for the absence of these assurances became more prevalent. Francis E. Leupp, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs between 1905 and 1908, wrote in favor of either a special court or some sort of extension of the Court of Claims to assess fairly the numerous Indian claims (Leupp, 1910, p. 196). The eventual creations of United States citizenship for Indians (An act to authorize the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians, 1924) and of the Indian Claims Commission (An act to create an Indian Claims Commission, to provide for the powers, duties, and functions thereof, and for other purposes, 1946) were manifestations of this activity.

Reliance upon the documents of negotiation between the tribes and the federal government thus became paramount for the courts. The expanded version of volume 2 (Kappler, 1904b) contains 388 documents, divided into two sections. A general treaty text portion holds 371 documents, consisting of 364 treaties recognized by the Department of State (Ratified Indian Treaties, 1722–1869, 1966) and of seven supplemental documents. Seventeen more items reside in an appendix, of which the first two are acknowledged instruments. [22]

Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, 1975 and 1979

In 1968, the Indian Civil Rights Act was passed. In the Title VII — Materials Relating to Constitutional Rights of Indians section of the Act, the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to "revise and extend" Kappler's compilation "to include all treaties, laws, executive orders and regulations relating to Indian Affairs in force on September 1, 1967" (An act to prescribe penalties for certain acts of violence or intimidation, and for other purposes, 1968, p. 81). This led to the creation of an additional 160 page supplement (Department of the Interior, 1975) to handle only the revisions made to federal regulations related to Indians; provisions in Title 25 — Indians of the Code of Federal Regulations were excluded from this publication. The Foreword (p. ii) stated: "The original and revised editions of Senate Document 319 of the 58th Congress, entitled Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties (popularly called "Kapplers") did not include federal regulations. Indeed, federal regulations were not available in the present codified form until 1935 when Congress directed a compilation of all documents of 'general applicability and legal effect.'" As a result, the publication included relevant regulations from twelve Titles of the Code of Federal Regulations. [23]

All five volumes were reprinted in 1975 by the Government Printing Office (Kappler, 1975). Physically, volume number 4 of this later edition had a page gap between Part VIII — Appendix and the place where the indexes for volumes 1 through 3 used to reside in the original 1929 rendition. The index for this new version began on page 1345, with the note "Indexes to Volumes I, II, and II, pp. 1195–1344, have been omitted."

The Department of the Interior subsequently published, in 1979, a sixth and a seventh volume, under the title Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties (Department of the Interior, 1979a and b). No further volumes have been created.

Case selection and Table I

View Table I (PDF File)

It is clear that his contributions to government were considerable, yet Kappler's later involvement as an attorney is impressive as well. The cases noted below have been accumulated to demonstrate his service within jurisprudence and were collated solely to identify his diversification. These proceedings are divided into two groups — those that cited American Indian treaties and those that did not — as one way to illustrate his skills and interests.

Locating Kappler's cases was achieved by interrogating the "Federal & State Cases, Combined" option of the full LexisNexis online database for COUNSEL (Kappler OR Merillat) cases. In a similar fashion, the ALLCASES option of the full Westlaw system was examined with the search element AT (Kappler Merillat). In this manner, Table I was constructed to identify, in total, 91 cases between 1904 and 1945. [24]

Table I is an aggregate of the following data:

- The attorney(s) in the case, where "K" denotes Kappler alone and "KM" is a joint Kappler & Merillat endeavor;

- The case title, where bolded examples appear again in Table II;

- The date of the decision;

- The reporter citation for this case;

- The court in which the case was heard. The venues are United States Supreme Court ("U.S. Sup. Ct. — N = 41); state Supreme Court ("Sup. Ct., Wash." and "Sup. Ct., Okla." — N = 2); Courts of Appeals ("D.C. Cir," "Cir. 8," and "Cir. 10" — N = 26); Circuit Court of Appeals ("Cir. Ct., W.D. Okla." — N = 1); Court of Claims ("Ct. Cl." — N = 19); or Tax Court ("Board of Tax Appeals" — N = 2);

- The presence — indicated by a check mark — of this suit in the case list of the major legal guides to federal Indian law created in the last sixty-five years:

- Cohen's Handbook of Federal Indian Law (1942; N = 28);

- the Department of the Interior's Federal Indian Law (1958; N = 20);

- the second edition of Cohen's compilation (Strickland, 1982; N = 12);

- the American Indian Law Deskbook (Smith, 2004; N = 4); and

- the third edition of Cohen's work (Newton, 2005; N = 6).

Table II

View Table II (PDF File)

With regard to his earlier compilation of Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Table II is composed of those twenty-eight cases taken from Table I that referred to one or more recognized Indian treaties, and is composed of the following data:

- the ratified treaty number for the document, as assigned by the Department of State (Ratified Indian Treaties, 1722–1869, 1966); [25]

- the treaty's title, identified by Kappler's designation from his second volume of Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties (1904b), followed by the citing case name(s);

- the date on which the treaty was signed;

- the instrument's page number in Kappler's second volume;

- the Statutes at Large citation for that document; and

- the page number of the treaty entry in the Schedule of Indian Land Cessions section of Indian land cessions in the United States (Royce, 1899). There is no entry in Royce's compilation for ratified treaty number 198 or 246, the Treaty with the Comanche, etc., 1835 and the Treaty with the Comanche, Aionai, Anadarko, Caddo, etc. , 1846.

Conclusion

Table I identifies the 91 cases in which Kappler participated. Of these suits, the 28 highlighted ones referred specifically to 38 of the 375 recognized treaties with the tribes (Ratified Indian Treaties, 1722–1869, 1966). Each of these 38 individual documents is paired with the case name of each citing suit from Table I to form the contents of Table II. For example, the third entry in Table II highlights ratified treaty number 43, the Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, 1804 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 74–77). Two cases in which Kappler participated — Sac and Fox Indians of Iowa v. Sac and Fox Indians of Oklahoma (1910) and Sac and Fox Indians of the Mississippi in Iowa v. Sac and Fox Indians of the Mississippi in Oklahoma (1911) — cited this specific treaty and so are collected together here. This strong linkage, between his personal interest in Indian affairs and his collation of what became the primary source for the final texts of recognized treaties with the tribes, is a reflection of the new approach taken with the tribes during the New Deal era. [26] This focus was also evident in the life and work of Felix S. Cohen. [27]

The presence of each specific treaty-citing proceeding was checked in the case lists of Cohen's original work on American Indian law (1942); of the revamped version of this collation by the Department of the Interior (1958); of a subsequent edition under the Cohen model (Strickland, 1982); of a newer presentation of these materials (Smith, 2004); and of the latest recasting of the Cohen approach (Newton, 2005). The last five columns of Table I mirror this analysis. These texts are the fundamental sources for the understanding of American Indian law and their inclusion of so many of Kappler's cases illuminates the place of this attorney at the very center of the development of this jurisprudence during the first half of the twentieth century.

Special attention should be drawn to six special situations.

-

First, Kappler was counsel for John Kenny — whose name was apparently misspelled before the Court — in the 1917 United States Supreme Court appearance, Kenney v. Miles (1917), while his former partner, Charles H. Merillat, was attorney for the respondents. [28] This was just a few years after the two had dissolved their partnership.

Briefly, in these proceedings, John Kenny successfully petitioned for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma. Before this state venue (Kenny v. Miles, 1917), the results of previous county and district court cases, regarding the partitioning of allotted and patented lands totaling 660 acres left upon the 1908 death of Lah-tah-sah, an enrolled Osage woman, were appealed. In both of the earlier actions, Kenny, her only child, maintained the position that he was the sole heir and should receive the entire property, while Miles, her surviving husband, asked for one-half of the land. Both were duly enrolled Osage members and the sole question before the district court was Miles's martial status with Lah-tah-sah. This standing was decided in favor of Miles, the lands were equally divided, and this distribution was made by the court. In the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, Miles contended that his wife's lands were selected after her death and "therefore such lands are neither homestead nor surplus, but constitute a separate and distinct class of allotment upon the alienation of which no restrictions were imposed by Congress" (Kenny v. Miles, 1917, p. 42). [29] The Court agreed and affirmed the district court's decision to equally divide and distribute the property.

Two years later, the suit was heard before, and decided in Kenny's favor by, the United States Supreme Court (Kenny v. Miles, 1919). The judgment from the Supreme Court of Oklahoma was reversed and defined "inoperative" (p. 65) because the lands in question were determined to be restricted and thus administrable under Congress's direction: "[w]e have seen that the provision of the Act of 1912 [30] under which the partition suit was brought and entertained declares that where the lands are restricted, as was the case here, no partition or sale of the restricted lands shall be valid until approved by the Secretary of the Interior" (p. 65; emphasis added). The importance of the role of the Secretary of the Interior in such Osage inheritance situations, as well as his responsibility to exchange effectively surplus allotments, were thus affirmed. Many such inheritance questions, and therefore court proceedings that involved attorneys such as Kappler and Merillat, were caused by the complexities resulting from the application of the General Allotment Act [31] that dispersed millions of acres of tribal lands.

-

Second, the Leonard (1925) précis for Kappler indicated a number of "leading cases." All but one of these is represented in Table I. The only exception of these important suits was Grace Cox (1913), an inheritance case involving Omaha trust lands that was decided by the Office of Indian Affairs at the Department of the Interior. The Twenty-seventh annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1905–1906 (1911) contains an article entitled "The Omaha Tribe" and an alphabetical index for the "Original Owners of Allotments on Omaha Reservation" (pp. 643–654) which indicates that Grace Cox's designated 40 acre allotment was number 1003. The accompanying "Title Map — Omaha Reservation, Thurston County, Nebraska" in that volume shows her holdings, northeast of the town of Pender, at T. 25 N., R. 7 E., sec. 19, SW¼ NE¼. The case revolved around "one person claiming as a "child" of the decedent, and two other persons denying that claim and contending that they are the decedent's heirs as half-sister and nephew of the "next of kin"" (Grace Cox, 1913, p. 495).

Felix Cohen (1942, p. 110) noted this specific case in the "Administrative Power — Individual Lands" section of his chapter on "The Scope of Federal Power Over Indian Affairs." Its importance lies in the application of An act to provide for determining the heirs of deceased Indians, for the disposition and sale of allotments of deceased Indians, for the leasing of allotments, and for other purposes (1910) that ensured that the Secretary of the Interior was "not bound by decree or decision of any court in inheritance proceedings affecting restricted allotted lands" (Cohen, 1942, p. 110), and that, according to the Act, "his decision thereon shall be final and conclusive" (1910, p. 855). [32] In Grace Cox, the Secretary exercised this authority and ruled "that the alleged status of adoptive parent and adopted child, as between Grace Cox and Jennie Woodhull, be not recognized" (Grace Cox, 1913, p. 502; emphasis original). [33] A number of subsequent court cases, challenging this power of the Secretary in such situations, failed to modify this capacity until 1990. [34]

There is no indication of Kappler's status in this opinion, [35] but this is another indication of his involvement in Indian trust land inquiries.

-

Third, Kappler was a petitioner and counsel in several income tax cases (Appeal of Owen [1926]; Norcross v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue [1933]; and Norcross v. Helvering [1935]) and as appellant, along with Charles H. Merillat, in an attorney substitution case (Kappler v. Sumpter, 1909). In an additional case pertaining to an unpaid legal fee (Kappler v. Storm, 1916), Kappler acted solely as plaintiff.

The Owen case concerned the question of whether a distribution by a corporation to its shareholders was taxable. Kappler, along with others in this appearance before the United States Board of Tax Appeals, was a shareholder in the Osage Natural Gas Company and his liability pertained to a $96.26 shortfall in income tax paid for the year 1919. The majority shareowner, Charles Owen, [36] had an exposure of $58,045.92, but there were others named in the list of sixteen taxpayers who owed less than Kappler. The court opinion identifies another attorney, as well as two Certified Public Accountants, on the legal team, so the effort must have been substantial. The appeal, however, was denied.

The Norcross pair regarded another income tax deficiency, of $250 for the year 1929. In these instances, Kappler and three others unsuccessfully approached the United States Board of Tax Appeals, and then the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, to exempt them from federal income tax on income paid by the state of Nevada.

It is interesting to note that Charles H. Merillat was involved in a personal tax case, as well. Merillat v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue (1927) discussed his alleged payment arrears of $884.11 for the 1921 tax year. It also indicated that, besides his law practice, "since about 1912, he also has been engaged in the business of leasing Indian oil lands in the State of Oklahoma" and that these transactions were with "the Otoe and Missouria Tribes of Indians" (p. 813). The question before the same Board of Tax Appeals was whether certain payments made by Merillat were rentals and so deductible. The tax shortfall was created when these payments were ruled nondeductible business expenses, but the Board determined that they were allowable and Merillat won his appeal.

In the attorney substitution suit — Kappler v. Sumpter (1909) — the proceedings revolved around two previous cases (Garfield v. United States ex rel. Goldsby, 1907 and 1908) which reversed the act of deletion by the Secretary of the Interior of John E. Goldsby's name, and ultimately the names of others, from the official Chickasaw Nation citizenship and allotment rolls. Three Sumpter family members were among the plaintiffs in Goldsby, but chose to file separate petitions for the same outcome. In the process, they acquired another attorney, William W. Wright, and discharged Kappler and Merillat, without informing them. Wright filed the necessary petition for Jacob D. Sumpter four months before Kappler and Merillat brought their suit in which they claimed that they had been inappropriately replaced. The Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia found that "[a] party to a suit may change his attorney when he sees fit, assuming the responsibility, of course, for his breach of his contract with his former attorney" (Kappler v. Sumpter, 1909, p. 408) and the appeal was dismissed.

The Storm event, on appeal before the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, involved an alleged shortfall of $100 due counsel for service in a prior Indian allotment case; the "judgment of the trial court [was] reversed and the cause remanded" (Kappler v. Storm, 1916, p. 1144).

Taken together, the Owen, Sumpter, and Storm scenarios provide further insight into Kappler, at the personal and at the professional level.

-

Fourth, in the briefs for three Court of Claims cases, Kappler referenced unratified treaties. In Rogers v. Osage Nation of Indians (1910), the opinion stated (p. 389): "On May 27, 1868, commissioners on the part of the United States signed a treaty with the Osage Nation of Indians, at Drum Creek, Kans., by the terms of which the Lawrence, Leavenworth and Galveston Railroad Company would have acquired the Osage trust land and the Osage diminished reserve, comprising about 8,000,000 acres of land, for the price of less than 20 cents an acre, to be paid for $100,000 in cash and $1,500,000 in bonds of the railroad company that were not a mortgage on the land conveyed for the deferred payments. The Drum Creek treaty of 1868 was a direct violation of the treaty of 1865 between the United States and the Osage Nation of Indians. The treaty commissioners had been offered and refused to accept a higher price than the railroad company was to pay." An examination of the briefs, filed by Kappler and Merillat for this case, reveals far more elements of the intrigue involved in this transaction.

A special jurisdictional act, as part of a huge appropriations bill, had empowered the Court to "render a judgment or decree against the Osage Nation of Indians for such amount, if any, as the court shall find legally or equitably due for these services of said Adair and Vann, either upon contract or upon a quantum meruit." [37] Both Adair and Vann were Cherokee tribal members and had worked successfully as attorneys to quash this transaction with the railroad, primarily as representatives of the Cherokee and, claimed in this suit, of the Osage as well. They were initially promised by the Osage $4.2 million for their services, based on the size of the proposed cession. This amount was not submitted to the Secretary of the Interior for approval, as required by law in 1872. [38] Ultimately, authorization was granted in 1874 for an amount of $50,000, but Rogers was brought as "a suit to recover an alleged balance due upon a written agreement for attorney's fees." This final agreement, totaling $230,000, had been endorsed by the Osage council in 1873 after the $4.2 million amount was considered by the attorneys themselves to be unwarranted for their services (Rogers v. Osage Nation of Indians, 1910, p. 391). [39] Sue M. Rogers was the wife, and the executrix of the estate, of William P. Adair, while her co-petitioner, Cullus Mayes, was the administrator of the estate of Clement N. Vann (Brief for Defendant, 1909, p. 844). They sought the remaining $180,000 from the last contract made with the Osage.

A House Report (Osage Indian treaty, 1868, p. 2) had remarked, just three weeks after the treaty signing, that "the Osages were improperly influenced to consent to the signing of said treaty; that they were very reluctant to execute it, and that at no time, before or since its execution, were they satisfied to sell their lands at such a price or upon such securities." The Court, forty years later, concluded that "[t]here were so many factors and so many and varied sources of influence brought to bear in a concerted effort to defeat this treaty that to award compensation to the claimants upon the theory of paramount or exclusive service would be an unjust perversion of Indian funds" (Rogers v. Osage Nation of Indians, 1910, p. 393). Further, it determined that the approved fee of $50,000 had been paid and accepted by the attorneys, in lieu of all claims for past services and as full payment, and so the case against the Osage was dismissed. In the efforts leading up to this opinion, however, Kappler and Merillat supplied the court with a particularly robust history of the sequence of events surrounding these attempted transactions. They demonstrated also that there was minimal, if any, evidence to support any real claim for relief for the alleged activities by these two attorneys as representatives of the Osage (Brief for Defendant, 1909, pp. 869–870 and 992–997). This included "the fact that they appeared publicly as representatives in hostility to the Osages" (p. 995; emphasis added).

This Drum Creek instrument was discussed at length in Congress, especially after the Osage Indian treaty House Report, went unratified, and thus never warranted recognition by the Department of State as a true treaty. Deloria and DeMallie (1999) included this contract in their "Treaties and Agreements Rejected by Congress" chapter and noted that this treaty "would have become a highly publicized scandal had it been ratified, because it would have transferred a large part of their lands to a railroad" (p. 746). [40] Such outrage may be found in another House Executive Document, Great and Little Osage Indians (1868), and this general negative attitude towards the entire transaction was confirmed finally through the withdrawal, by President Ulysses S. Grant on 4 February 1870, of the Drum Creek treaty and three similar proposals that questioned the policy of selling Indian land to corporations (Brief for Defendant, 1909, p. 880). [41]

In Indians of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation v. the United States (1930), citation was made to the Treaty with the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa from 27 July 1866 (Deloria and DeMallie, 1999, pp. 1379–1383), also called the Agreement at Fort Berthold, 1866 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 1052–1056). This suit was expedited by the special jurisdictional act of 11 February 1920 [42] that permitted "all claims of whatsoever nature which any or all of the tribes of Indians of the Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota, may have against the United States, which have not heretofore been determined by the Court of Claims" (p. 404). This unratified document provided provisions, beyond those expressly initiated by the Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 594–596), for the Arikara and — through a supplemental Addenda — for the Gros Ventre and the Mandan. Specifically, this treaty was cited as support for the tribes' claim for $50,000 for timber "taken, used, or destroyed by settlers, citizens, soldiers and steamboat companies of the United States" and because the federal government had the duty "to protect Petitioners and the timber belonging to them upon the reservation guaranteed them" (Amended Petition, 1924, p. 30). The government countered by claiming an offset [43] — in part, "$290,827.25, alleged to be pro rata cost of educating individual children of the bands at various nonagency Indian schools" (Indians of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation v. the United States, 1930, p. 340) — but the court ruled to restrict such deductions to $2,753,924.89 and found for the tribes a net award of $2,169,168.58 from the original award amount of $4,923,093.47.

Finally, Crow Nation v. the United States (1935) before the Court of Claims [44] addressed the issue of the taking of Crow lands by the federal government. [45] The special jurisdiction act authorizing these proceedings noted the Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851 and the Treaty with the Crows, 1868 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 594–596 and pp. 1008–1011, respectively), made solely with the Mountain Crow, was fundamental to the question. Another branch of the Crow tribe, the River Crow, were forced on to the smaller reservation through the action of the latter transaction made with the Mountain Crow and thereby lost their lands pledged through the Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851, to which they were a party. [46] As the Crow Nation opinion states (p. 248): "About 1859 a portion of the Crow Tribe or Nation left that section of the country where the entire tribe had lived, viz., the reservation provided for it by the Fort Laramie treaty of 1851, and occupied the country along the Missouri River and its northern tributary, the Milk River, outside the boundaries of the territory recognized by the Fort Laramie treaty of 1851 as belonging to the Crow Nation. Thereafter those living along the Missouri and Milk Rivers became known as the River Crows, and those remaining in the reservation as Mountain Crows."

The petition was filed by the Crow Nation or Tribe of Montana "for and on its own behalf and also and especially for and on behalf of the River Crow branch of the Crow nation or tribe" to sue "the United States as defendant in and for that, notwithstanding it was known to the United States that the River Crow branch of the Crow nation or tribe was not a party to the aforesaid treaty dated May 7, 1868 [i.e., the Treaty with the Crows, 1868], Defendant deprived the River Crow tribe without compensation of any and all right, title or interest in and to the lands granted the entire tribe by the Fort Laramie treaty of 1851" (Petition, 1927, p. 19). Kappler, as lead counsel, referred to the outcome of Fort Berthold, to the 13 July 1868 unratified Treaty with the Gros Ventre (Deloria and DeMallie, 1999, pp. 937–940 and Kappler, 1913, pp. 705–708), and to the 15 July 1868 unratified Treaty with the River Crow (Deloria and DeMallie, 1999, pp. 941–944 and Kappler, 1913, pp. 714–716) [47] to support this claim. In this specific situation, these two unratified documents were linked: the River Crow were allocated reservation lands through article three of the treaty made two days earlier with the Gros Ventre. [48] In the process, the original land reserved for the Crow through the Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851 shrunk from 38.5 million to 8 million acres. Plaintiffs petitioned for $30 million in compensation for this loss or, in the alternative, at least $12 million for the River Crow. Both requests were rejected, and federal set-offs — totaling $3,627,954.93 — cancelled out any other possible monetary claims.

An examination of Shepard's Federal Citations (2006) reveals that Rogers has never been referenced again, while Indians of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation and Crow Nation have been cited in numerous later cases. Clearly, though, these three appearances before the Court of Claims — and especially, the second and third — illuminate Kappler's grasp of all relevant negotiations between the tribes and the government, whether the transactions were recognized by the Department of State or not. The exposure to treaty manipulation and, in these specific examples, to the use of unratified instruments to twist the valid ones; to the prospect of fee gouging, as demonstrated in Rogers, through "a pretended contract between these claimants and the Great and the Little Osage Indians" (Payments from the sale of Osage Indian lands, 1878; emphasis added); to the crippling penalty of receiving unconscionable considerations for, on top of losing, their lands to railway companies; and to the humiliating stigma of taking almost any handout from the federal government that could be presented later in court as "gratuitous," brought home to the tribes the vast gulf that would never be addressed without a better avenue through the courts, especially given the added burden of a special jurisdictional act by Congress required to even present their case in a federal venue. These battles in the early twentieth century would result in the Indian Claims Commission, [49] and would provide the tribes with one final opportunity to secure justice. This latter journey, begun in the late 1940s, finally ended on 27 September 2006, when the Pueblo de San Ildefonso Claims Settlement Act of 2005 was signed into law, [50] thereby addressing the final remaining Indian Claims Commission docket and ending a trek lasting half a century that involved almost every recognized tribe or band.

-

Fifth, the decisions for the last two listed federal cases in which Kappler participated were separated by less than a month. They were the Northwestern Bands of Shoshone Indians v. United States proceedings, before the United States Supreme Court in March and April 1945, with the latter one a denied rehearing request. [51] Wilkins (1997, pp. 136—165) discussed extensively the previous history, the opinions of the Justices in the March 1945 outcome, and the number of inconsistencies in those remarks that made more clouded the logic applied to the result. The use of the Shoshone suite in this note, though, is one of exhibition. Kappler was 76 years old at the time, but these efforts were the culmination of his activities on behalf of the tribes, as well as a model of court cases that solidified the creation of the Indian Claims Commission.

Beginning in 1926, Merillat and Kappler had undertaken the task to seek compensation for the taking of Shoshone lands (Wilkins, 1997, p. 143), but the bands had to wait for a special jurisdictional act to allow them to file suit against the federal government. Such permission was unnecessary for non-Indians, who could apply unimpeded to the United States Court of Claims for redress, but tribes — with their treaty-based proceedings — required these authorizations to gain access to the Court.

In 1929, such an act was passed for these Bands' complaint. [52] They filed suit in the Court of Claims in 1931 to recover $15 million for the taking of more than 15 million acres of their lands. [53] The Court, in 1942, ruled that the Bands were not entitled to this relief, on the grounds that the jurisdictional act demanded that the court consider only aspects of the 30 July 1863, Treaty with the Shoshoni — Northwestern Bands, 1863 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 850–851) and that the tribe's claims for compensation had to be one "arising under or growing out of" that treaty or related documents (45 Stat. 1407). It did, however, indicate that the Bands were due $10,804.17 in lost annuities, pledged in Article 3 of the Treaty with the Shoshoni — Northwestern Bands, 1863 (p. 850). In 1944, Kappler was "on brief" for a findings case considering that amount (see Table I for the citations for both of these March 1942 and the January 1944 cases). The government demonstrated that it had made $10,816.48 in gratuitous expenditures on behalf of the Bands. This offset amount eliminated any chance of recovery. [54]

Appeals of Court of Claims decisions rested with the Supreme Court and the Brief for Petitioners (1944) to that jurisdiction, with Kappler "of counsel," systematically laid out in eighty pages the reasons to overturn the Court of Claims results. The Brief presented over eighty relevant court cases and — with special reference to Kappler — 101 references to sixty-one treaties from his volume 2 of Indian Affairs. [55] Crow Nation and Indians of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, as part of a barrage of 82 cited cases, were employed as demonstrations of supporting law for the Band's petition to recover. The Supreme Court was not convinced by these arguments and — with the twists and turns of their opinion that are enumerated by Wilkins (1997) — the case was closed. An immediate request for a rehearing, in April 1945, was denied, even after an amicus curiae brief submitted by the American Civil Liberties Union that, besides questioning the grounds of the earlier outcome, warned that "[w]here minorities suffer, the community at large is the loser" (Brief of the American Civil Liberties Union in Support of Petition for Rehearing, 1945). After roughly two decades, the Northwestern bands were not compensated for either their lost lands or annuities. Kappler died the following January.

-

As the last point, Table I indicates the numerous, recurring citations to Kappler's cases made by various handbooks of federal Indian law issued in the last six decades. Of special interest here are the twenty Kappler cases cited in the Department of the Interior's Federal Indian Law (1958). This monograph, published twelve years after his death, was created with a mandate to discredit the seminal work of Felix S. Cohen, the Handbook of Federal Indian Law (1942), [56] yet these suits involving Kappler — many conducted during the prime of the New Deal years — could not be disregarded. The third paragraph of the Introduction to Federal Indian Law (1958, p. 1), in an unmasked declaration of support for the government's tribal termination policy of the 1950s, stated: "Much of the earlier Federal law and many Indian treaties now have only historical significance. As national development and progress continue and as new patterns of policy evolve, legal answers to questions of Federal Indian law will be found predominately in the latest statutory law and jurisdictional determinations of justiciable issues. Those are stressed in this revision for the purpose not only of seeking balance, to the extent practicable, but also for the purpose of foreclosing, if possible, further uncritical use of the earlier edition by judges, lawyers, and laymen."

This criticism certainly must have been proposed, in part, to counter the New Deal-era perspective evident in the Foreword of Cohen's 1942 volume: "This Handbook of Federal Indian Law should give to Indians useful weapons in the continual struggle that every minority must wage to maintain its liberties, and at the same time it should give to those who deal with Indians, whether on behalf of the federal or state governments or as private individuals, the understanding which may prevent oppression" (Cohen, 1942, p. v). Cohen had formulated the Wheeler-Howard or Indian Reorganization Act [57] in 1934 that served as the pinnacle of New Deal Indian Affairs legislation. The creation of tribal constitutions, as forwarded by the Act, was a far cry from the approach engendered in the termination policies of the 1950s. [58]

Further, in an echo of the 1946 obituary citing Kappler's skills (Charles Kappler Dies; Expert and Writer on Indian Affairs, 1946), and just two years before the appearance of Federal Indian Law, United States Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren called Cohen "an acknowledged expert in Indian law" (Squire v. Capoeman, 1956, p. 8). The Introduction to the second edition of Cohen's work (Strickland, 1982). emphasized again that Federal Indian Law was written when termination was in the forefront of federal Indian policy, and as such, Cohen's work had "proved embarrassing" (p. ix). It was also concluded that Interior's revision "did not reflect Felix Cohen's work," that his "carefully considered conclusions were omitted," that cautiously crafted historical analyses were "discarded," and that "the scholarship of the 1958 edition was inadequate."

In the early 1990s, another resource bought together the outcomes of the adjudication of Federal Indian law during the previous decade. Its primary focus was on "[t]he states, particularly those in the West . . . [that] encounter issues of Indian law with far more frequency than most entities," and because "Indian law has become a major part of the business of the offices of the western attorneys general" (Smith, 2004, p. xxi). Because of this enduring concern, the initial American Indian Law Deskbook has now evolved into a third edition, carrying on the positive example that Cohen had set six decades earlier.

Finally, in 2005, the third edition of the Handbook of Federal Indian Law was published (Newton, 2005). Its size — over 1400 pages in twenty-two chapters — was a direct indicator of the evolution of federal Indian law. Cohen's "focus and coherence to this confusing welter of sources" (p. ix) has been carried forward to support his desire to protect and encourage tribal status and development. The growth these days — much like that prior to the 1982 edition — is so intense that updates to the 2005 Handbook are projected, thereby avoiding the long lapses that stymied the understanding of federal Indian law.

Absent all the difficulties involved in the production of these handbooks over the last sixty-five years, federal Indian law remains founded upon the legislation that sustained the contents of the 375 treaties created prior to 3 March 1871 by the British and the United States governments and now recognized by the Department of State. Cohen, in his bibliography (1942, p. 638), cited just four sources for "Collections of Treaties:" the three 19th century items that Commissioner of Indian Affairs Jones had found lacking — Indian Treaties, and Laws and Regulations Relating to Indian Affairs (1826); Treaties between the United States of America and the Several Indian Tribes, From 1778 to 1837 (1837); and A Compilation of All the Treaties between the United States and the Indian Tribes Now in Force as Laws (1873) — and Kappler's collation. [59]

Charles J. Kappler lived during a very critical period for federal Indian law. He was born just months after the final recognized treaty was signed with the Nez Perce, [60] and his life spanned seventeen Presidents — from Andrew Johnson to Harry S. Truman — each of whom struggled to some degree with American Indian issues. The linkage among Kappler's desire, and the mandate instilled by the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, to collect the scattered documents of the interactions between the Indian Nations and the federal government; a major proportion of his own legal career during the period of New Deal reforms; Felix S. Cohen's vision of a sound and well understood federal Indian law; and virtually all litigation [61] involving the tribes since the creation of the United States is premised upon the assurances contained in those legal instruments. Without Kappler's ensemble of the final texts of these critical documents and his efforts in their application, the turmoil within this broad area of jurisprudence would have been far worse over the last century.

References

A Compilation of All the Treaties between the United States and the Indian Tribes Now in Force as Laws. (1873). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

A New Company. (1898). The Washington Post, 25 January 1898, 9.

A Short History of a Very Round Place. (1990). The Washington Post, 2 September 1990, SM19.

Amended Petition. (1924). The Indians of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in the State of North Dakota, Comprising the Tribes Known as the Arickarees, the Gros Ventres, and the Mandans, and the Individual Members Thereof, Petitioners vs. The United States of America, Defendant. Brief before the Court of Claims, No. B-449, filed 31 July 1924.

Amendment No. 1574. (1990). Congressional Record 136(7), 9193–9195.

An act conferring jurisdiction upon the Court of Claims to hear, adjudicate, and render judgment in claims which the northwest bands of Shoshone Indians may have against the United States. (1929). 45 Stat. 1407.

An act conferring jurisdiction upon the Court of Claims to hear, examine, adjudicate and render judgment in claims which the Crow Tribe of Indians may have against the United States, and for other purposes. (1926). 44 Stat. 807.

An act for the division of the lands and funds of the Osage Indians in Oklahoma Territory, and for other purposes. (1906). 34 Stat. 539.

An act making appropriations for the current and contingent expenses of the Indian Department and for fulfilling treaty stipulations with various Indian tribes for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, nineteen hundred and four, and for other purposes. (1903). 32 Stat. 982.

An act making appropriations for the current and contingent expenses of the Indian department, and for fulfilling treaty stipulations with various Indian tribes, for the year ending June thirty eighteen hundred and seventy-two, and for other purposes. (1871). 16 Stat. 544.

An act making appropriations for the current and contingent expenses of the Indian Department, for fulfilling treaty stipulations with various Indian tribes, and for other purposes, for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, nineteen hundred and seven. (1906). 34 Stat. 325.

An act regulating the mode of making private contracts with Indians. (1872). 17 Stat. 136.

An act supplementary to and amendatory of the act entitled "An act for the division of the lands and funds of the Osage Nation of Indians in Oklahoma," approved June twenty-eighth, nineteen hundred and six, and for other purposes. (1912). 37 Stat. 86.

An act to amend the Indian Land Consolidation Act to improve provisions relating to probate of trust and restricted land, and for other purposes. (2004). 118 Stat. 1773.

An act to authorize the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians. (1924). 43 Stat. 253.

An act to confer to the Court of Claims jurisdiction to determine the respective rights of and differences between the Fort Berthold Indians and the government of the United States. (1920). 41 Stat. 404.

An act to conserve and develop Indian lands and resources; to extend to Indians the right to form business and other organizations; to establish a credit system for Indians; to grant certain rights of home rule to Indians; to provide for vocational education for Indians; and for other purposes. (1934). 48 Stat. 984.

An act to create an Indian Claims Commission, to provide for the powers, duties, and functions thereof, and for other purposes. (1946). 60 Stat. 1049.

An act to incorporate the Oak Hill Cemetery, in the District of Columbia. (1849). 9 Stat. 773.

An act to make miscellaneous amendments to Indian laws, and for other purposes. (1990). 104 Stat. 206.

An act to prescribe penalties for certain acts of violence or intimidation, and for other purposes. (1968). 82 Stat. 73.

An act to provide for determining the heirs of deceased Indians, for the disposition and sale of allotments of deceased Indians, for the leasing of allotments, and for other purposes. (1910). 36 Stat. 855.

An act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes. (1887). 24 Stat. 388.

An act to reduce the fractionated ownership of Indian lands, and for other purposes. (2000). 114 Stat. 1991.

An act to resolve certain Native American claims in New Mexico, and for other purposes. (2006). 120 Stat. 1218.

Andrew, J. A. (1992). From Revivals to Removal: Jeremiah Evarts, the Cherokee Nation, and the Search for the Soul of America. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Annual report of Anson G. McCook, Secretary of the United States Senate, showing the receipts and expenditures of the Senate from July 1, 1889, to June 30, 1890. (1890). Senate. 51st Congress, 2nd session. Senate Miscellaneous Document No. 2 (Serial Set 2819). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Annual report of Charles G. Bennett, Secretary of State, submitting a full and complete statement of the receipts and expenditures of the Senate from July, 1901, to June 30, 1902. (1902). Senate. 57th Congress, 2nd session. Senate Document No. 1 (Serial Set 4416). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Annual reports of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1899, Indian Affairs, Part I. (1899). House of Representatives. 56th Congress, 1st session. House Document No. 5, pt 2-1 (Serial Set 3915). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Annual reports of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1900. Indian Affairs. Report of Commissioner and Appendixes. (1900). House of Representatives. 56th Congress, 2nd session. House Document No. 5, pt 2-1 (Serial Set 4101). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Annual reports of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1901. Indian Affairs. Part I. Report of the Commissioner, and appendixes. (1901). House of Representatives. 57th Congress, 1st session. House Document No. 5, pt 2-1 (Serial Set 4290). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Appeal of Owen, 3 B.T.A. 905 (1926).

Appendix II. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1902. United States vs. Mexico. In the Matter of the Case of the Pious Fund of the Californias. (1903). House of Representatives. 57th Congress, 2nd session. House Document No. 1 (Serial Set 4442). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Application for admission to practice. (1956). Admissions Paper No. 33674. Records of the Supreme Court of the United States (RG 267). Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration.

Arenas v. United States, 95 F. Supp. 962 (1951).

Arenas v. United States, 197 F.2d 418 (1952).

Ballinger v. United States ex rel. Frost, 216 U.S. 240 (1910).

Bernholz, C. D. (2004). American Indian treaties and the Supreme Court: A guide to treaty citations from opinions of the United States Supreme Court. Journal of Government Information 30, 318–431.

Bernholz, C. D. (2007). American Indian treaties and the lower federal courts: A guide to treaty citations from opinions of the lower United States federal court system. Government Information Quarterly 24, 443–469.

Bernholz, C. D. and Holcombe, S. L. (2005). The Charles J. Kappler Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Internet site at the Oklahoma State University. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 29, 82–89.

Bernholz, C. D. and Weiner, R. J. (2005). American Indian treaties in the state courts: A guide to treaty citations from opinions of the state court systems. Government Information Quarterly 22, 440–488.

Bernholz, C. D. and Weiner, R. J. (2008). American Indian treaties in the Courts of Claims: A guide to treaty citations from opinions of the United States Courts of Claims. Government Information Quarterly 25, 313–327

Bernholz, C. D.; Pytlik Zillig, B. L.; Weakly, L. K.; and Bajaber, Z. A. (2006). The last few American Indian treaties – An extension of the Charles J. Kappler Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Internet site at the Oklahoma State University. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 30, 47–54.

Birth Control Wins Favor, Group Told. (1940). The Washington Post, 3 April 1940, X12.

Births Reported. (1916). The Washington Post, 20 December 1916, 12.

Blanset v. Cardin, 256 U.S. 319 (1921).

Bond v. United States, 181 F. 613 (1910).

Bow to Society Made at Dance By Miss Kappler. (1936). The Washington Post, 29 December 1936, X12.

Brief for Defendant. (1909). Sue M. Rogers, as Executrix of the Estate of William P. Adair, and Cullus Mayes, as Administrator of the Estate of Clement N. Vann, Petitioners, vs. The Osage Nation of Indians, Defendant. Brief before the Court of Claims, No. 29,607, filed 1 December 1909.

Brief for Petitioners, 1944 WL 42546 (1944).

Brief for the United States, 1944 WL 42547 (1944).

Brief of the American Civil Liberties Union in Support of Petition for Rehearing, 1945 WL 48324 (1945).

Certificate of Death. (1912). Belle S. Kappler, 8 July 1912, No. 206071, Washington, DC.

Certificate of Death. (1946). Charles J. Kappler, 20 January 1946, No. 461017, Washington, DC.

Certificate of Death. (1949). Katherine S. Kappler, 4 May 1949, No. 488966, Washington, DC.

Charles J. Allen: Letter from the Assistant Clerk of the Court of Claims transmitting a copy of the findings of the Court in the case of Charles J. Allen, United States Army, retired, against the United States. (1912). Senate. 62nd Congress, 3rd session. Senate Report No. 969 (Serial Set 6366). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Charles J. Kappler, Prominent Washington Attorney, Adopted into Crow Indian Tribe. (1931). The Hardin Tribune-Herald, 21 August 1931, 1.

Charles Kappler Dies; Expert and Writer on Indian Affairs. (1946). The Evening Star, 21 January 1946, B4.

Charles Kappler is Authority on Indian Laws and Treaties. (1941). The Evening Star, 6 July 1941, C8.

Charles T. Kappler. (1942). U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938–1946. Retrieved from Ancestry.com on 19 May 2007.

Charles T. Kappler. (1993). The Washington Post, 3 November 1993, D5.

Claims of the Northeastern Bands of Shoshone Indians. (1928). Senate. 70th Congress, 1st session. Senate Report No. 519 (Serial Set 8830). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Clement N. Vann and William P. Adair. (1906). House of Representatives. 59th Congress, 1st session. House Report No. 2904 (Serial Set 4908-E). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Cohen, F. S. (1942). Handbook of Federal Indian Law, with Reference Tables and Index. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Cohen, F. S. (2007). On the Drafting of Tribal Constitutions. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Compilation on Indian Affairs. (1902a). Congressional Record 35, 5619.

Compilation on Indian Affairs. (1902b). Congressional Record 35, 5664–5665.

Conroy, S. B. (1990). The Flourishing Spirit of Dumbarton Oaks. The Washington Post, 4 November 1990, F1.

Convention between the United States of America and the Republic of Mexico, for the adjustment of claims. (1868). 15 Stat. 679.

Cornwell, J. R. (1995). From hedonism to human rights: Felix Cohen's alternative to nihilism. Temple Law Review 68, 197–221.

Cowen, W.; Nichols, P.; and Bennett, M. T. (1978). The United States Court of Claims: A History, Part II: Origin — Development — Jurisdiction: 1855–1978. Washington, DC: Committee on the Bicentennial of Independence and the Constitution of the Judicial Conference of the United States.

Crow Eagle, 40 Pub. Lands Dec. 120 (1911).

Crow Nation v. the United States, 81 Ct. Cl. 238 (1935).

Daily, D. W. (2004). Battle for the BIA: G.E.E. Lindquist and the Missionary Crusade Against John Collier. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Deloria, V. and DeMallie, R. J. (1999). Documents of American Indian Diplomacy: Treaties, Agreements, and Conventions, 1775–1979. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Department of Labor. (1931). List of United States citizens. S.S. President Harrison, Los Angeles, 19 July 1931.

Department of Labor. (1934). List of United States citizens. S.S. President Roosevelt, New York, 15 September 1934.

Department of the Interior. (1880a). 1880 Census — District of Columbia. Series T9, roll 123, 109.

Department of the Interior. (1880b). 1880 Census — District of Columbia. Series T625, roll 205, 230.

Department of the Interior. (1900). 1900 Census — District of Columbia. Series T623, roll 158, 36.

Department of the Interior. (1958). Federal Indian Law. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Department of the Interior. (1975). Supplement to Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties: Compiled Federal Regulations Relating to Indians. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Department of the Interior. (1979a). Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, vol. 6. Laws: Compiled from February 10, 1939 to January 13, 1971, Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Department of the Interior. (1979b). Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, vol. 7. Laws: Compiled from February 10, 1939 to January 13, 1971, Part II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Died. (1912). The Washington Post, 9 July 1912, 3.

Doyle, J. T. (1906). In the International Arbitral Court of The Hague: The Case of the Pious Fund of California. San Francisco, CA: Geo. Spaulding & Co.

Elliott, R. R. (1983). Servant of Power: A Political Biography of Senator William M. Stewart. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press.

Far Away. (1930). The Washington Post, 27 April 1930, SMA7.

Feldman, S. M. (1986). Felix S. Cohen and his jurisprudence: Reflections on federal Indian law. Buffalo Law Review 35, 479–525.

First Moon v. White Tail, 270 U.S. 243 (1926).

Forgey, B. (1987). Preservation with Personality: The Sensitive Restorations of the Southern and Bond Buildings. The Washington Post, 19 December 1987, D1.

From the President. (1897). The Washington Post, 1 June 1897, 4.

Gaffey, J. P. (1976). Citizen of No Mean City: Archbishop Patrick Riordan of San Francisco, 1841–1914. Wilmington, DE: Consortium Books.

Garfield v. United States ex rel. Goldsby, 30 App.D.C. 177 (1907).

Garfield v. United States ex rel. Goldsby, 211 U.S. 249 (1908).

Golding, M. P. (1981). Realism and functionalism in the legal thought of Felix S. Cohen. Cornell Law Review 66, 1032–1057.

Gompers v. Buck Stove & Range Co., 221 U.S. 418 (1911).

Grace Cox, 42 Pub. Lands Dec. 493 (1913).

Great and Little Osage Indians. (1868). House of Representatives. 40th Congress, 2nd session. House Executive Document No. 310 (Serial Set 1345). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Halford, A. J. (1901). Official Congressional directory for the use of the United States Congress. First edition. Corrected to December 5, 1901. Senate. 57th Congress, 1st session. Senate Document No. 4, part 1-3 (Serial Set 4221). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Hallowell v. Commons, 239 U.S. 506 (1916).

Handbook Prepared On Indian Law. (1940). The Washington Post, 5 August 1940, 11.

Hearings before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on matters relating to the Osage Tribe of Indians. (1909). Senate. 60th Congress, 2nd session. Senate Document No. 744 (Serial Set 5409). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Heckel, J. W. (1968). Questions and answers. Law Library Journal 61, 313–316.

Hesselman, G. J. (1913). Digest of Decisions of the Department of the Interior in Cases Relating to the Public Lands, vol. 1–40. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Hoffman, A. (1997). Inventing Mark Twain: The Lives of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. New York: William Morrow and Co.

Home Missions Council of North America. (1944). Indian Wardship. New York: Home Missions Council.

Hubbell's Legal Directory for Lawyers and Business Men. (1906). New York: Hubbell Publishing Co.

Hubbell's Legal Directory for Lawyers and Business Men. (1909). New York: Hubbell Publishing Co.

Hubbell's Legal Directory for Lawyers and Business Men. (1914). New York: Hubbell Publishing Co.

Indian Heirship Policy Adopted. (1913). Christian Science Monitor, 27 October 1913, 10.

Indian treaties. (1904). 33 Stat. 2077.

Indian Treaties, and Laws and Regulations Relating to Indian Affairs. (1826). Washington, DC: Way & Gideon.

Indians of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation v. the United States, 71 Ct. Cl. 308 (1930).

Instructions on the Sale of Lands by Heirs of Moses Agreement Allottees, 40 Pub. Lands Dec. 212 (1911).

Investigation of Indian contracts. Hearings before the Select Committee of the House of Representatives appointed under authority of House Resolution No. 847, June 25, 1911, for the purpose of investigating Indian contracts with the Five Civilized Tribes and the Osage Indians in Oklahoma. (1911). House of Representatives. 61st Congress, 3rd session. House Report No. 2273, pt. 2 (Serial Set 5854). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Johnson, K. M. (1963). The Pious Fund. Los Angeles, CA: Dawson's Book Shop.

Kappler v. Storm, 153 P. 1142 (1916).

Kappler v. Sumpter, 33 App.D.C. 404 (1909).

Kappler, C. J. (1892). The Record and Services of Hon. Wm. M. Stewart in the Senate of the United States since His Election in 1887: Speech of Mr. Chas. J. Kappler before the Stewart and Newlands' Club, Reno, Nevada, October Twenty-Ninth, 1892.

Kappler, C. J. (1896). Entry term minutes, 1863–1938, vol. 8, 234. Records of the District Courts of the United States (RG 21). Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration.

Kappler, C. J. (1901). Entry 61, Attorney rolls, 1790–1961. Records of the Supreme Court of the United States (RG 267). Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration.

Kappler, C. J. (1903a). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties, vol. 1. Statutes, executive orders, proclamations, and statistics of tribes. Senate. 57th Congress, 1st session. Senate Document No. 452, pt. 1 (Serial Set 4253). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kappler, C. J. (1903b). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties, vol. 2. Treaties. Senate. 57th Congress, 1st session. Senate Document No. 452, pt. 2 (Serial Set 4254). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kappler, C. J. (1904a). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties, vol. 1. Laws. Senate. 58th Congress, 2nd session. Senate Document No. 319, pt. 1 (Serial Set 4623). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kappler, C. J. (1904b). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties, vol. 2. Treaties. Senate. 58th Congress, 2nd session. Senate Document No. 319, pt. 2 (Serial Set 4624). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kappler, C. J. (1913). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties, vol. 3. Laws. Senate. 62nd Congress, 2nd session. Senate Document No. 719 (Serial Set 6166). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kappler, C. J. (1929). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties, vol. 4. Laws. Senate. 70th Congress, 1st session. Senate Document No. 53 (Serial Set 8849). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kappler, C. J. (1941). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties, vol. 5. Laws. Senate. 76th Congress, 3rd session. Senate Document No. 194 (Serial Set 10458). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kappler, C. J. (1972a). Indian Treaties: 1778–1883. Mattituck, NY: Amereon House.

Kappler, C. J. (1972b). Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, vol. 1–5. New York: AMS Press.

Kappler, C. J. (1973). Indian Treaties: 1778–1883. New York: Interland Publishing.

Kappler, C. J. (1975). Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, vol. 1–5. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Kaufman, S. B.; Albert, P. J.; and Palladino, G. (1999). The Samuel Gompers Papers, vol. 7 — The American Federation of Labor under Siege, 1906–1909. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Kenney v. Miles, 244 U.S. 653 (1917).

Kenny v. Miles, 65 Okla. 40 (1917).

Kenny v. Miles, 250 U.S. 58 (1919).

Kimball, E. M. (1962). Digest of Decisions of the Department of the Interior in Cases Relating to the Public Lands, vol. 52–61. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Leonard, J. W. (1925). Who's Who in Jurisprudence: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Lawyers and Jurists, 1925, with a Complete Geographical Index. Brooklyn, NY: John W. Leonard Corp.

Leupp, F. E. (1910). The Indian and His Problem. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Little Chief, 40 Pub. Lands Dec. 102 (1911).

Mack, E. M. (1964). William Morris Stewart, 1827–1909. Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 7, 1–121.

Maddex, D. (1985). Master Builders: A Guide to Famous American Architects. Washington, DC: Preservation Press.

Marriage Registry. (1896). Old St. Mary's Church, Washington, DC, 64.

Martin, J. E. (1995). "A year and a spring of my existence:" Felix S. Cohen and the Handbook of Federal Indian Law. Western Legal History 8, 35–60.

Martin, J. E. (1998). The miner's canary: Felix S. Cohen's philosophy of Indian rights. American Indian Law Review 23, 165–179.

Martindale's American Law Directory. (1899). New York: J.B. Martindale.

Martindale's American Law Directory. (1919). New York: J.B. Martindale.

McKinley May Distribute the Diplomas. (1897). The Washington Post, 25 May 1897, 3.

Merillat v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 9 B.T.A. 813 (1927).

Message of the President of the United States withdrawing certain Indian treaties. (1870). Senate. 41st Congress, 2nd session. Senate Confidential Executive Document L. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Michael, W. H. (1889). Official Congressional directory for the use of the United States Congress. First edition. Corrected to December 5, 1889. Senate. 51st Congress, 1st session. Senate Miscellaneous Document No. 13 (Serial Set 2697). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Michael, W. H. (1890). Official Congressional directory for the use of the United States Congress. First edition. Senate. 52nd Congress, 1st session. Senate Miscellaneous Document No. 1, part 1–3 (Serial Set 2903). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Miss Julia Claud Becomes Bride of Mr. Kappler. (1951). The Washington Post, 29 April 1951, S12.

Miss Shuey a Bride. (1909). The Washington Post, 17 February 1909, 7.

Miss Suzanne Kappler is Wed to Lieut. James E. Palmer, Jr. (1943). The Washington Post, 12 October 1943, B4.

Mitchell, D. T. (2007). Architect of Justice: Felix S. Cohen and the Founding of American Legal Pluralism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Moore v. United States, 32 Ct. Cl. 593 (1897).

Mrs. K. Shuey Kappler Dies Here at 61. (1949). The Evening Star, 5 May 1949, A26.

New Lawyers Admitted to Bar. (1896). The Washington Post, 13 December 1896, 14.

Newton, N. J. (2005). Felix S. Cohen's Federal Indian Law. Newark, NJ: LexisNexis/Matthew Bender.

Nimrod v. Jandron, 24 F.2d 613 (1928).

Norcross v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 1933 5358 (1933).

Norcross v. Helvering, 64 App.D.C. 160 (1935).

Northwestern Bands of Shoshone Indians v. United States, 325 U.S. 840 (1945).

Official Register of the United States, containing a list of the officers and employés in the civil, military, and naval service on the first of July, 1889; together with a list of vessels belonging to the United States. Volume I. Legislative, executive, judicial. (1890). House of Representatives. 51st Congress, 1st session. House Miscellaneous Document No. 41, part 1 (Serial Set 2764). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Official Register of the United States, containing a list of the officers and employés in the civil, military, and naval service on the first of July, 1891; together with a list of vessels belonging to the United States. Volume I. Legislative, executive, judicial. (1892). House of Representatives. 52nd Congress, 1st session. House Miscellaneous Document No. 50, part 1 (Serial Set 2985). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.